April 21, 2025

Janan Boehme, Winchester Mystery House Historian

San Jose was recently chosen as one of the top-ten eco-conscious cities in the U.S., Greenest Cities in America (2025). Though you may think of ecological awareness as a modern phenomenon, it’s been around for a long time. Let’s look at what was going on in California during Sarah Winchester’s lifetime, and see how she fit into the ecological picture after moving here.

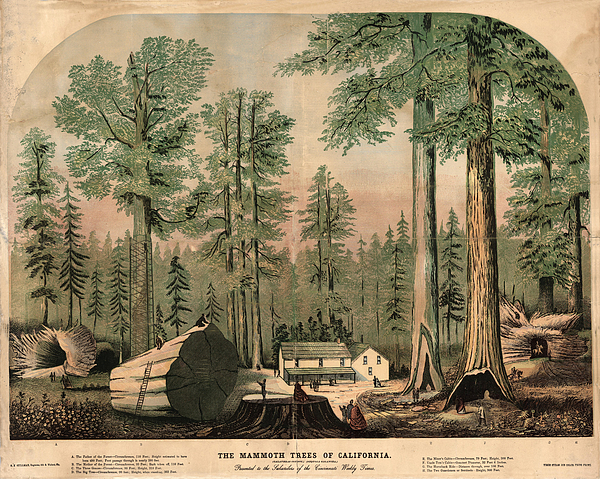

In 1851, when Sarah was a young girl of 12 growing up in New Haven, Conn., Americans were already pushing the government to preserve national forestlands.¹ Many were furious in 1852, when a 2,500-year-old giant redwood, named “Mother of the Forest,” was stripped of its bark in California (in what would later become Yosemite National Park) so its shell could be reconstructed and displayed in New York and London.

Calaveras Grove sequoias in California, including Mother of the Forest, before 1860. (Public Domain)

The bark of a giant California redwood, called “Mother of the Forest” reconstructed in the Crystal Palace in London, 1859. (Public Domain)

The tree, deprived of its protective bark, ultimately died. New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley condemned the act as “vandalism.” A few years later, Greeley toured the west and was stunned by the beauty of the Yosemite Valley, which he called “the most unique and majestic of nature’s marvels.”²

In 1864, two years after Sarah married William Winchester, California Senator John Conness introduced a bill in Congress aimed at protecting the Yosemite Valley. The bill was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln in June of that year. By the time the widowed Sarah bought her ranch in California’s Santa Clara Valley in 1886, the state’s ancient and majestic old-growth redwoods were being ruthlessly clearcut to build rapidly growing towns and cities, and many Californians started to worry about their survival.

By 1899, Sarah had been in the Santa Clara Valley for about 13 years. Andrew P. Hill—a San Jose landscape painter and photographer who had taken a studio portrait of Sarah’s niece Marion, as well as one of Sarah’s beloved dog Zip—was commissioned to photograph a grove of old-growth redwoods in Felton, about 30 miles southwest of Sarah’s San Jose home. Hill was so amazed by the ancient giants, and so appalled at the thought of them becoming building lumber and railroad ties that he vowed to save as many as he could.

He invited some influential Bay Area citizens to go camping with him in the “Big Basin” area of the Santa Cruz Mountains, and the result was the creation of the Sempervirens Club, whose motto was “Save the Redwoods.” Its members worked tirelessly—and successfully—to turn Big Basin into California’s first state park.³ Sadly, by that time, only about 25% of California’s old-growth redwoods remained.

“The Commissioners Prospecting and Investigating for Big Basin Park,” 1901, by A. P. Hill (Courtesy History San Jose)

Fund-raising was key to Sempervirens’ success, and Hill encouraged Sarah to contribute to the cause. She gave $500—a generous contribution even today, and a very large sum indeed back at the turn of the last century!

Although the buildings on Sarah’s estate—including the mansion—were built of redwood (the go-to lumber in California) her fruit ranch did contribute to the ecological health of the valley. Her ranch was part of a vast agricultural empire that supplied fruits and vegetables to the rest of the country, as well as other parts of the world. She had more than 100 acres under cultivation with prune, apricot, and walnut trees, and she also created a lush 18-acre botanical garden around the mansion. This densely planted acreage created a natural carbon sink, pulling unhealthy carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and pumping oxygen back into it!

Orchards on Sarah Winchester’s estate. (Courtesy History San Jose)

Sarah also had systems in place that helped replenish the valley’s water table (a vast underground aquifer that supplied water for the valley’s wells and orchards). Her builders created a complex gutter and drainage system that collected the rainwater that fell on and around the mansion, as well as the excess water from houseplants that were watered in her specially designed North and South Conservatories, and on her balconies and terraces. Water was carried away from the mansion through a maze of pipes (saving the foundation from rot and subsidence), funneled through a series of brick-lined catch-basins, and eventually into dry wells around the estate. From these, it could percolate back down into the water table—a beautiful recycling system!

Three different “catch basins” routing water under Sarah’s estate.

Re-purposed lumber was used by Sarah’s carpenters to build new bathroom walls in the Crystal Bedroom Suite.

References:

¹ Mother Of The Forest, Environmental History

² National Parks: The American Experience (Chapter 1) (nps.gov)

³ https://sempervirens.org/about/story/