“This is the richest valley in the world …”

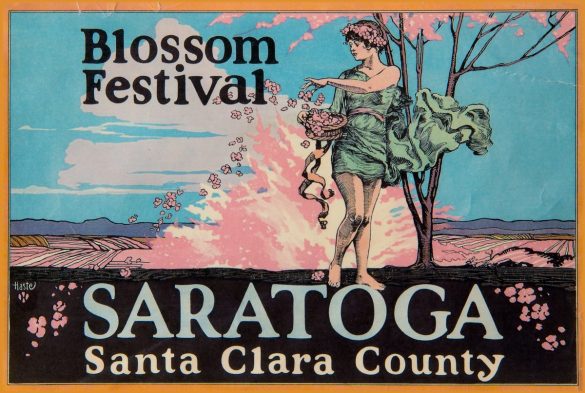

That’s how one U.S. senator described Silicon Valley—only it wasn’t the personal wealth of the region that Chauncey M. Depew was referring to when he spoke those words nearly 120 years ago. It was the dirt beneath his feet. The soil was so productive that, in the spring, after blossoms blanketed the valley with their perfume, they ripened into sweet cherries, apricots, pears, and figs.

One of the nation’s most productive agricultural regions, the Valley of Heart’s Delight, or the Santa Clara Valley, is where Sarah Pardee Winchester laid down her own roots in 1886. With the help of a cadre of orchard and farm managers, she sowed a quarter million trees on acreage producing over 150,000 pounds of prunes, apricots and walnuts in a season.

This botanical heritage, a rare remnant in Silicon Valley, is worth visiting in modern San Jose. At the Winchester Mystery House, it’s not just indoors but outdoors where you can see ideas borrowed from many international expositions and the Victorian gardening trends. In today’s dollars, what you see cost about $38 million to bring it to light (or about $1.5 million 133 years ago).

A secret Victorian garden

In the 1880s, those fortunate enough to receive an invitation to Llanada Villa (Sarah’s name for her estate) would enter on a road lined with stately Yucca palms.

Then, they could easily lose themselves in the classic English gardens, wandering pathways defined by hedges and framed by trellises and arbors, with benches strategically placed for time-outs—all trademark embellishments of the Victorian era. In the aviary and hothouse, rare birds fluttered among a collection of orchids. For culinary pleasure, a juicy-fruit paradise ripened and included grapes, blackberries, lemons, oranges, grapefruits, figs and persimmons.

According to records, the gardens are defined as English with French statuary. But Llanada Villa also sprinkled in worldliness. Depending on where you stood, the vibe might read Rhodes or Rome, Kyoto or Cornwall, California desert or Portugal’s Douro. Plant species spanned an estimated 110 countries.

Spartan junipers, cherry laurels, and boxwood hedges were staples; all were fast growers that could give privacy and easily be shaped for an artistic flair—a Victorian trait.

While Sarah herself favored standards like geraniums and daisies, the zeitgeist was flowers, creepers and vines that opulently twisted, bloomed, perfumed, and texturized the outdoors, an alluring botanical kingdom. And San Jose, aka “the Garden City,” was a dream: It was a hub for nurseries. One of the largest, Navlet’s, opened in 1885, trading in chrysanthemums, sweet peas, passiflora, hyacinths, carnations, creeper trumpets, jasmine, and roses, oh so many roses—climbing, ramblers, antique, Bourbon, shrubs, miniatures.

In January 1894, the California Midwinter International Exposition rolled into Golden Gate Park with a Japanese village and tea garden exhibit that inspired Sarah to re-create her own version. The garden bug bit hard that year. According to the records, it was around that same year that Sarah financed a garden-supply shop in Mountain View for her sister’s husband to run.

When, in 1917, Kitazawa Seed Company opened in San Jose, it fulfilled the Victorian craving for Japanese horticultural curiosities. A number of years earlier, Sarah had hired a Japanese gardener, Tommie Nishihara, to manage her extensive gardens.

Nearly a century has passed since Tommie Nishihara tended the outdoor spaces, and many elements have been lost to time. But not everything. You’ll still come across the statue of a Native American gazing across the gardens at a stately buck, allegedly commissioned by Sarah to placate those killed by the Winchester rifle.

Flanking the entrance are statues of Hebe and Demeter, Greek goddess of youth and the harvest, beckoning. A few fruit trees continue to unfurl spring blossoms, purple blooms pop from thick wisteria vines in summer, and, from the mouth of frogs, trickles water into the fountain. A visit to these gardens erase, if for a moment, the sounds of the future zipping and zooming around Silicon Valley. What more could you ask for in an afternoon but to step back into the Valley of Heart’s Desire?